More than 350 years after this tragic event, there are still rumours of restless souls roaming the village. Unexplained footsteps apparently resound around the Miner’s Arms pub, but in a town where many houses have signs with the names of the victims on them, it is impossible to know whose footsteps they are. Or it’s probably just pure imagination …

Shortly after Jan van Riebeeck first arrived at the southern tip of Africa to establish a refreshment station for ships on their way to the far east, England was plagued by one of the biggest humanitarian disasters ever recorded. It was 1665 and London, in particular, was hard hit by the Great Plague – the bubonic plague. The plague was spread by fleas, which lived on rats, and the overpopulation, especially in poorer parts contributed to the deadly pandemic that rapidly spread among humans. The plague reached large parts of the country, especially urban areas such as York, while the countryside was left relatively unaffected.

For the inhabitants of Eyam, however, the plague would have tragic consequences and would set the stage for a human drama in which the suffering and selfless actions of the inhabitants of this small rural town would steer history in a different direction.

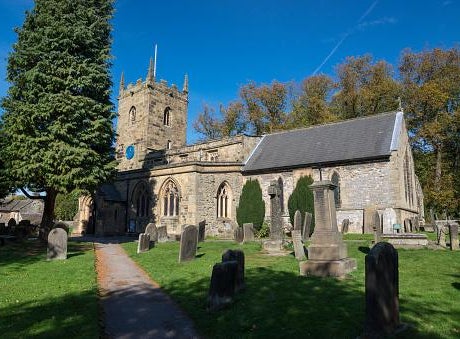

Around the time when planning for the construction of the castle in the Cape of Good Hope began in earnest, a bale of cloth was delivered from London to Eyam. It was late August of 1665. The picturesque Eyam, an Anglo-Saxon village in Derbyshire’s Peak District (just half an hour’s drive from where we live) had a population of about 800 souls at the time and was pest-free up to that point.

The consignment of cloth was delivered to the local tailor. The tailor’s assistant, George Viccars, saw that the material was damp and unbundled the bale of cloth to dry in front of the fire. However, the bale was full of plague-carrying fleas. George was the first resident to die a few days later.

The plague raged through the small community and by December, 42 people were dead. By the end of winter, in March 1666, many residents began packing their belongings, ready to leave town.

Summer dawned and as this terror began to spread like wildfire in the summer sun, the villagers took an incredible, courageous stance to save others from the same fate.

On June 24, 1666 the rector, William Mompesson, with the help of another pastor, Thomas Stanley, urged the residents to quarantine themselves so that the disease could not spread to neighbouring settlements.

Despite being aware of a possible painful and horrific death that awaited them, the whole town promised to sacrifice their lives to prevent the plague from claiming more lives outside the village.

By August, a year after the bale was delivered, the scorching heat of an unusually hot summer had driven the villagers to despair.

Mothers buried their own children and husbands buried their wives while outsiders watched from a nearby hill – too scared to get closer to the inhabitants of the plague village.

Mompesson said his wife, Catherine, noticed a sickly, sweet smell in the air the day before she also died. He also told how letters from outsiders described the stench of “sadness and death” rising from the village.

In November 1666, the plague claimed its last victim in Eyam without spreading to neighbouring communities. Eyam’s sacrifice saved countless lives.

The small town lost 260 of its inhabitants to the Great Plague. It is estimated that 200,000 people died across England.

A well-known children’s song (with different variations) has its origins in this terrible period. When you hear the song again, think of the inhabitants of Eyam.

Ring-a-ring o ‘roses,

A pocket full of posies,

A-tishoo! A-tishoo!

We all fall dead.

Dankie, vir die deel van hierdie. Baie interessant.