AUTUMN IN MY VALLEY – THE AMBER VALLEY, DERBYSHIRE.

“Notice that autumn is more the season of the soul than of nature.”

Friedrich Nietzsche

More than 350 years after this tragic event, there are still rumours of restless souls roaming the village. Unexplained footsteps apparently resound around the Miner’s Arms pub, but in a town where many houses have signs with the names of the victims on them, it is impossible to know whose footsteps they are. Or it’s probably just pure imagination …

Shortly after Jan van Riebeeck first arrived at the southern tip of Africa to establish a refreshment station for ships on their way to the far east, England was plagued by one of the biggest humanitarian disasters ever recorded. It was 1665 and London, in particular, was hard hit by the Great Plague – the bubonic plague. The plague was spread by fleas, which lived on rats, and the overpopulation, especially in poorer parts contributed to the deadly pandemic that rapidly spread among humans. The plague reached large parts of the country, especially urban areas such as York, while the countryside was left relatively unaffected.

For the inhabitants of Eyam, however, the plague would have tragic consequences and would set the stage for a human drama in which the suffering and selfless actions of the inhabitants of this small rural town would steer history in a different direction.

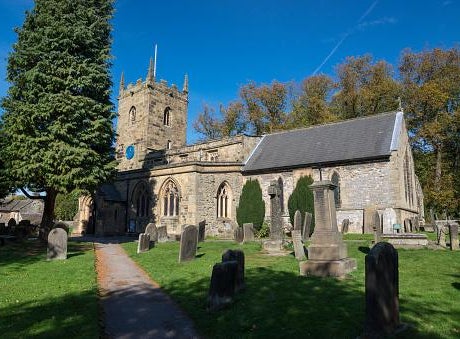

Around the time when planning for the construction of the castle in the Cape of Good Hope began in earnest, a bale of cloth was delivered from London to Eyam. It was late August of 1665. The picturesque Eyam, an Anglo-Saxon village in Derbyshire’s Peak District (just half an hour’s drive from where we live) had a population of about 800 souls at the time and was pest-free up to that point.

The consignment of cloth was delivered to the local tailor. The tailor’s assistant, George Viccars, saw that the material was damp and unbundled the bale of cloth to dry in front of the fire. However, the bale was full of plague-carrying fleas. George was the first resident to die a few days later.

The plague raged through the small community and by December, 42 people were dead. By the end of winter, in March 1666, many residents began packing their belongings, ready to leave town.

Summer dawned and as this terror began to spread like wildfire in the summer sun, the villagers took an incredible, courageous stance to save others from the same fate.

On June 24, 1666 the rector, William Mompesson, with the help of another pastor, Thomas Stanley, urged the residents to quarantine themselves so that the disease could not spread to neighbouring settlements.

Despite being aware of a possible painful and horrific death that awaited them, the whole town promised to sacrifice their lives to prevent the plague from claiming more lives outside the village.

By August, a year after the bale was delivered, the scorching heat of an unusually hot summer had driven the villagers to despair.

Mothers buried their own children and husbands buried their wives while outsiders watched from a nearby hill – too scared to get closer to the inhabitants of the plague village.

Mompesson said his wife, Catherine, noticed a sickly, sweet smell in the air the day before she also died. He also told how letters from outsiders described the stench of “sadness and death” rising from the village.

In November 1666, the plague claimed its last victim in Eyam without spreading to neighbouring communities. Eyam’s sacrifice saved countless lives.

The small town lost 260 of its inhabitants to the Great Plague. It is estimated that 200,000 people died across England.

A well-known children’s song (with different variations) has its origins in this terrible period. When you hear the song again, think of the inhabitants of Eyam.

Ring-a-ring o ‘roses,

A pocket full of posies,

A-tishoo! A-tishoo!

We all fall dead.

Many years from now, future historians will be scratching their heads to figure out how the mass suicide in 2020 was sanctioned. And how was it possible that so many so-called developed countries, with the legacy of Nobel Prize-winning scientists and advanced technology at their disposal, were still caught with their pants down by a virus?

And, yes, by suicide, I mean actual suicide, but also the destruction of our livelihood, driving businesses into liquidation and damaging our mental state.

This article should be read in tandem with my previous post (The Emperor is Naked) where it was emphasised from the outset that I am not against the lockdown. On the contrary. I think it is the best way to contain the virus. My concern is about the way this lockdown is been managed.

In 1978, Jim Jones, leader of an American cult in the Guyanese jungle, ordered his followers to murder a US congressman and several journalists, then commit mass suicide by drinking cyanide-laced fruit punch.

His followers, some acceptant and serene, others probably coerced, queued to receive cups of cyanide punch and syringes. The children were poisoned first, and can be heard crying and wailing on the commune’s own audio tapes, later recovered by the FBI.

In total 909 followers of Jones, including 304 children, died that day.

Decades later, survivors of the tragedy still remember being part of an organization that they devoted a good portion of their lives to. “The people were incredible,” says Jean Clancey. “People who were capable of committing themselves to something outside of their own self-interests.”

“We – all of us – were doing the right things but in the wrong place with the wrong leader,” adds Laura Johnston Kohl.

Tim Carter said, “There were so many lies that Jones told to people to create a state of siege mentality in the community, that even those that were making ‘a principled stand of revolutionary suicide’ probably were influenced a lot by the lies that he was telling them.”

Leslie Wagner-Wilson, told Fox News: “There’s a need. People want to be a part of something. They want to feel safe; they want to feel a sense of community.

“In an environment like this”, Ms Wagner-Wilson cautions, “you might think there’s something wrong, but because everyone else is embracing it and clapping and being joyous, you look at yourself and say, ‘It must be me’”.

Familiar key words, aren’t they? Incredible people, committed, do the right thing, sense of community, feel safe, clapping and being joyous, etc.

At the time, after hearing about this horrible mass suicide for the first time, I was thinking to myself, how on earth is it possible for so many people to be influenced by one man? How can a parent feed their crying, unwilling children poison and then commit suicide? It’s madness.

Now, in 2020 I wonder no more. I’m experiencing it.

Currently, an estimated 2.6 billion people – one-third of the world’s population – is living under some kind of lockdown or quarantine. This is arguably the largest psychological experiment ever conducted.

Unfortunately, we already have a good idea of its results. In late February 2020, right before European countries mandated various forms of lockdowns, The Lancet , a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal , published a review of 24 studies documenting the psychological impact of quarantine. The findings offer a glimpse of what is brewing in hundreds of millions of households around the world.

In short, and perhaps unsurprisingly, people who are quarantined are very likely to develop a wide range of symptoms of psychological stress and disorder, including low mood, insomnia, stress, anxiety, anger, irritability, emotional exhaustion, depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Low mood and irritability specifically stand out as being very common, the study notes.

In just a two week period, suicide was the leading cause for over 338 “non-coronavirus deaths” in India due to distress triggered by the nationwide lockdown – 151 people killed themselves due to loneliness, withdrawal symptoms and financial distress.

It is estimated that up to 150,000 Britons could die from non-coronavirus causes, caused by a spike in suicides and domestic violence, because of the UK’s lockdown. The pandemic is expected to have a huge knock-on effect on people’s mental health due to financial worries and a disruption to routine. As early as 6 April, it was published that an increasing number of mental health incidents had been reported to police.

The new-normal that we are trying to maintain is unsettling, in troubling and intense ways. Unnerving, because we really don’t know what tomorrow will be like. Apparently, for humans, living with uncertainty is harder than living with pain. According to writer and psychotherapist, Bryan Robinson, participants in an experiment who were told they would definitely receive a painful electric shock were calmer than those who were told that they had a 50% chance of receiving one. Our brains, argues Robinson, are wired to equate uncertainty with danger.

No wonder solitary confinement – being used in prisons to keep unruly prisoners in check – receive so much criticism for having detrimental psychological effects and, to some and in some cases, constituting torture.

In South Africa, the national government’s Gender-based Violence Command Centre recorded more than 120 000 calls from victims who rang the national helpline for abused women and children in the first three weeks after the lockdown started – double the usual volume of calls.

The damage that COVID-19 is causing is irrefutable, but so are the effects of the lockdown. As a global community we are united in following these restrictions despite its adverse affects – such is the power of the ‘herd mentality’. Indeed, it is the only solution we have until a vaccination is found, but it doesn’t mean that we have to resign ourselves to the worst of these conditions. Perhaps our leaders can take a leaf from a publication in The Lancet, titled “The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it”:

Stay safe!

IN THE DEPTH OF WINTER, I FINALLY LEARNED THAT THERE WAS IN ME AN INVINCIBLE SUMMER – Albert Camus.

EARLY MONDAY MORNING AFTER A DRENCHED WEEKEND.

DAY MONDAY MORNING AFTER A DRENCHED WEEKEND

DAY MONDAY MORNING AFTER A DRENCHED WEEKEND

HIGH PEAK JUNCTION

The early bird catches … a stunning sunrise on a crisp early-autumn morning.

“The High Peak Junction, near Cromford, Derbyshire, England, is the name now used to describe the site where the former Cromford and High Peak Railway (C&HPR), whose workshops were located here, meets the Cromford Canal. It lies within Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site.” (Wikipedia).

The sunset is not too shabby too.